Tuesday, September 6, 2016

Tuesday, June 28, 2016

Is it FEAR you’re afraid of?

While mowing my lawn listening to Switchfoot on Spotify, I paused for a second as Jon Foreman sang the lyrics, “is it fear you’re afraid of?” Had to think about that line for a second. How many times are we afraid? Afraid of change. Afraid of living. Afraid of risks. Afraid of fear. Some people live in constant fear. Sad really, when fear takes hold of a heart, driving people to irrational anxiety or worry to the point of not living. I’ve been there myself.

As a child, my parents would send me downstairs to fetch something for them. Being the oldest child, it seemed that responsibility fell to me more often than my siblings. I hated going downstairs by myself. Some people love the isolation and quiet of the basement, but not me. It was one of my greatest fears. I was convinced there were people downstairs just under the stairs ready to grab my ankles through the open stairwell. To make matters worse, the light switch was at the top of the stairs. On more than one occasion, one less than sympathetic family member found it funny to turn the light off while I was downstairs. Fumbling my way through the dark I would clamour sniggling

Years later, my fear turned to full blown anxiety when I found myself working in a group home trying to put myself through college. As much I told myself that I didn’t need to be afraid of those kids, my irrational fear could not control the thought patterns I had trained my mind to think. I felt so out of control and afraid. It took a lot of reading, self-reflection, journaling, and talking to finally change those patterns.

That was over 30 years ago. Over the years, I have used my weaknesses and failures as a means to empathize with my students in the classroom. As teachers, Parker Palmer reminds us that we “try to teach to their fearful hearts” so they can be freed up to learn and change their hearts. How many of our students struggle to come to school each and every day? Fear is fear, irrational or not. It still bottles people up limiting them from really living. Nothing drives me crazier than watching unsympathetic and uncaring individuals ignorantly go about their daily affairs, so wrapped up in their selfish lives, oblivious of people suffering from fear. And even worse, when it’s kids who are suffering!

It takes very little for us to smile and say hello. It takes very little to stop and engage in conversation. It takes very little to give of our time to make another feel of some importance or significance. It takes very little in comparison to a lifetime to stop and listen to the heartbeat of a child’s soul echoing its sad refrain. Yet if it takes so little, what stops so many of us from giving a little of ourselves to ease the child’s fearful suffering.

I think truth be told, many of us have yet to master the fear we have within ourselves. We are still afraid of fear. We are afraid to die, we afraid to live, we are afraid to fail, we are afraid to succeed, we are afraid to lose, we are afraid to win, we are afraid of change, we are afraid things staying the same. The list goes on. But we downplay the power fear has over us when we don’t acknowledge how much it controls us.

“As soon as our own safety is threatened, we tend to grab the first stick or gun available, telling ourselves that our survival is what really counts even if thousands of others are not going to make it. Aren’t we so insecure that we will snatch at any form of power that gives us a little bit of control over who we are, what we do, and where we go?

“I know my sticks and guns. Sometimes my stick is a friend with more influence than I; sometimes my gun is money or a degree; sometimes it is a little talent that others don’t have; and sometimes it is special knowledge, or a hidden memory, or even a cold stare

I am not afraid to say that I still live in fear, but I have acknowledged it, talked it through with loved ones, embraced a growth mindset that doesn’t feel shame for being afraid. I may still be afraid of fear, but I don’t let it stop me from living. I use fear to keep me alert to the dangers in life, not to force me into hiding. I don’t keep it all bottled up inside anymore. I’m honest about what it did to me. I’m not ashamed of it because I’ve had to push passed it. I allow myself to feel things and not become so detached and calloused. I let myself be human. So, yes, it is FEAR that I’m afraid of. Truth be told, we’re all afraid. But can we all admit it

Karen Thompson Walker

Tuesday, June 21, 2016

I Dared to Gaze Off into the Sunset…

How often do we fail to stop and appreciate what we have in life? We get so mired in the negative. So much is lost of time because we fail to adjust our attitudes. If you were to ask me how I was doing a couple of weeks ago, I wouldn’t have replied with much positive, because all I could see, feel, breath was the noxious negativity that I found myself in. Every time I opened my mouth I hated what I heard myself saying. I was frustrated and angry. I could choose to remain in this state of mind, or I could lose myself in the beauty of nature and space to regain perspective.

So for the past three weekends, we have gone camping. A time to get away and reflect. A time to read and escape into a world of fiction and fantasy. A time to rest and get away from the demands of life. A time to refresh and feed my soul. A time to heal from all the hurtful things hurled at me. A time to forgive and release the bitterness that encompassed my being.

And then on one of these camping excursions, a sunset rests gently into that goodnight that reminds you that everything will be okay. The winds still. The glassy mirroring water shimmers tranquillity for those willing to stop and dare to gaze off into the sunset to lose themselves for the next few minutes. Peace floods my soul. I am in awe and wonder of such beauty that the toxic tentacles evaporate into oblivion unable to maintain its hold on my heart. I want to feel love, not hate. I want to care despite the hurt and pain of rejection and failure. I am free to love because I choose to let the negative go.

May you dare to gaze off into the sunset and find some peace too!

Sunday, June 12, 2016

Love and Learning Go Hand in Hand

I was reading this morning from 1 Corinthians 13 this morning. Not to get all spiritual on everyone, I was, however, drawn into thought about the centrality of love with regard to schools and learning. As a teacher, if all l focus on is covering the curriculum outcomes without a love for the student, or a care for their situation in life, I may get results, but not near the results I would with love.

Let’s break this down. I’ve copied the passage that so many of us are familiar with from the numerous summer weddings we have attended. “Love is patient, love is kind, it does not envy, it does not brag, it is not puffed up, it does not behave inappropriately, it does not seek its own way, it is not provoked, it keeps no account of wrong, it does not rejoice over injustice but rejoices in the truth; it bears all things, it believes all things, it hopes all things, it endures all things. Love never fails.” 1 Corinthians 13:4–8 TLV

The teacher that loves the students, from a place so deep that cares for their being and the whole child, gets results beyond the curricular outcomes. That teacher puts the students needs before their own. That teacher is patient with all the frustrating and repeating negative behaviours of the student. That teacher shows kindness in return to rude comments and doesn’t keep a record of wrongdoings by the student. That teacher doesn’t think themselves better than any students but is grateful for the opportunity to positively influence and change a life. That teacher doesn’t dig in their heels against change because they want their own way, they put students first. That teacher doesn’t label students lazy when the student underperforms , instead, they look for ways to engage the student and build a healthy trusting relationship where learning can happen. That teacher embraces their own failures as well as the students so that they can both learn together. That teacher believes that students can learn and bears that responsibility to ensure every student is given that opportunity. That teacher possesses a hope that every student will grow up with a passion for learning and growing. No matter what happens in and out of the classroom, that teacher endures all things until retirement day still believing in students and wanting the best for them. Why? Because that teacher knows that love never fails.

I was talking to a friend and colleague recently, and he shared a story about going into a Principals office and being the question, “Whose the most important people in the school?” He replied, “The students.” The principal made the buzzing sound you hear when you give a wrong answer and said, “Wrong, the teachers are the most important.” I’m saddened by that principal’s perspective, because when we as teachers, administrators, and staff put students and their needs first, we all benefit in the end. In my school, students are the most important. Why? Because I love my students. I want them to learn. Love and learning go hand in hand.

You think about that.

Thursday, June 9, 2016

What Makes a School Great? Whole School Approach to Learning

I want to start by saying, Bassano School is a great school. It’s a great school for a number of reasons.

First of all, Bassano School has a great history of educating children. Some of you may have been so fortunate to have attended Bassano School fifteen, twenty, or even fifty years ago. I love walking the hallways in the high school and looking at the photographs of past graduates. Whether you attended in the past or not, I think we can agree that Bassano School has established quite a legacy of giving students opportunities to advance themselves beyond Grade 12 if they so chose. But our school isn’t made great simply because of what it did in the past, we must continue to stir the minds of students for learning. If all we strive for is to educate students as our primary goal, we have missed our purpose. We want to teach students how to learn as a lifelong pursuit. If all we dois equip students with the tools to learn how to think for themselves, learn new things as they grow, and know how to work, we have reached a great goal. So we are not in the business to educate as in a task to be completed, but rather we are a school that teaches students how to be learners.

Second, Bassano School is a great school because we challenge students and teachers alike to love learning. We want each person in our School to become independent, critical thinkers. We’re even okay with students arguing their point of view, albeit respectfully. Our task as teachers is not to teach students to submit to strict compliance. Our oldest daughter was the compliant child. She did exactly what she was supposed to do most of the time. She may not have agreed with what was asked of her, but she dutifully complied. That’s not what I wanted for her because so often I found that she was living her life to please us as parents and not living out her passions, her own dreams. Not unlike our students, we want them to add their ownflavour and style to their learning. Learning needs to be relevant to their own lives in order for it be meaningful. The learning isn’t limited to students. As teachers, we need to be reflective in our teaching and learning. It requires us to stretch ourselves and ask the important questions of why we teach the way we do or do our assessment more fairly. If we want students to love learning, we need to love learning too and model it for our students.

Third, Bassano School is a great school because we believe that students and teachers alike are important. We believe that we cannot teach a child unless we foster an environment for relationship building with students. We need to be transparent mentors that can admit to failures and mistakes. Students need to know they can fail and still make things right and move forward. That’s why we allow students to do rewrites,redos , and retakes for tests and assignments. We encourage students and teachers to work together and find ways to demonstrate learning. We believe that every learner can learn, it’s only a matter of when they will learn.

Fourth, Bassano School is a great school because we celebrate the diversity of race, religion, and orientation. We promote respect for all types of learners. We make no distinction between those with money and resources and those with little or no accumulated wealth. Everyone is treated with equality and fairness. We will not condone a sense of entitlement to dictate the future of our school. We live in a transient society with people coming and going in and out of our community. Everyone’s opinion matters, whether they have a short-term relationship with the school or have been here for a lifetime. We may not agree with one another, but we will respect the opinions of others with open-mindedness and tolerance.

Finally and most importantly, Bassano School is a great school because we have a caring and kind group of students in our school. We may have our conflicts from time to time, but that’s life. We will listen to students first before jumping to conclusions. We will hear every side out and try to talk things out before making decisions. We don’t expect perfection from our students, but we expect effort. Try, fail, try again, fail again, try harder and succeed. Not every student is destined for college or university, but we will make sure everyone is assisted in finding out what they want to do after school. We will listen to make sure students don’t fall through the cracks. Everyone is important and has value to us as a school.

First of all, Bassano School has a great history of educating children. Some of you may have been so fortunate to have attended Bassano School fifteen, twenty, or even fifty years ago. I love walking the hallways in the high school and looking at the photographs of past graduates. Whether you attended in the past or not, I think we can agree that Bassano School has established quite a legacy of giving students opportunities to advance themselves beyond Grade 12 if they so chose. But our school isn’t made great simply because of what it did in the past, we must continue to stir the minds of students for learning. If all we strive for is to educate students as our primary goal, we have missed our purpose. We want to teach students how to learn as a lifelong pursuit. If all we do

Second, Bassano School is a great school because we challenge students and teachers alike to love learning. We want each person in our School to become independent, critical thinkers. We’re even okay with students arguing their point of view, albeit respectfully. Our task as teachers is not to teach students to submit to strict compliance. Our oldest daughter was the compliant child. She did exactly what she was supposed to do most of the time. She may not have agreed with what was asked of her, but she dutifully complied. That’s not what I wanted for her because so often I found that she was living her life to please us as parents and not living out her passions, her own dreams. Not unlike our students, we want them to add their own

Third, Bassano School is a great school because we believe that students and teachers alike are important. We believe that we cannot teach a child unless we foster an environment for relationship building with students. We need to be transparent mentors that can admit to failures and mistakes. Students need to know they can fail and still make things right and move forward. That’s why we allow students to do rewrites,

Fourth, Bassano School is a great school because we celebrate the diversity of race, religion, and orientation. We promote respect for all types of learners. We make no distinction between those with money and resources and those with little or no accumulated wealth. Everyone is treated with equality and fairness. We will not condone a sense of entitlement to dictate the future of our school. We live in a transient society with people coming and going in and out of our community. Everyone’s opinion matters, whether they have a short-term relationship with the school or have been here for a lifetime. We may not agree with one another, but we will respect the opinions of others with open-mindedness and tolerance.

Finally and most importantly, Bassano School is a great school because we have a caring and kind group of students in our school. We may have our conflicts from time to time, but that’s life. We will listen to students first before jumping to conclusions. We will hear every side out and try to talk things out before making decisions. We don’t expect perfection from our students, but we expect effort. Try, fail, try again, fail again, try harder and succeed. Not every student is destined for college or university, but we will make sure everyone is assisted in finding out what they want to do after school. We will listen to make sure students don’t fall through the cracks. Everyone is important and has value to us as a school.

Monday, May 16, 2016

Why is it so Hard to Change our Assessment Practices?

My forte is talking about character education, behavioural challenges, student issues when it comes to addressing personal struggles that are interfering with learning, and integrating technology into the classroom effectively and meaningfully. Often as a young teacher, when I heard we were going to talk about assessment I felt like the person on the left. I'm by no means an assessment expert, although I have read more than my fair share of assessment experts' books, blogs, watched tons of videos, and attended conferences with Rick Wormeli, Doug Reeves, and Dylan Wiliam, and I understand and now practice a Standards Based or Outcomes Based philosophical approach. Before coming to Alberta last year, I thought I was just an ordinary educator from Saskatchewan, who was using and implementing outcomes-based assessment in the classroom largely because I thought most teachers were doing the same everywhere across Western Canada. However, I've come to realise over the past year and a half, that is not the case at all. Most teachers are very good at teaching to the outcomes. They know their material, they teach the concepts, students are learning, and we are seeing success. So it isn't so much in the teaching that we have our challenges. But aligning assessment practices to teaching outcomes is not happening in a consistent fashion across schools, divisions, and the province. I had my struggles with implementing outcomes-based assessment at first, but I made the change because it was the right and fair thing to students.

Approximately eight years ago, I was put to the test about my assessment philosophy. I say philosophy because I was a district administrator at the time, and not directly in a K-12 classroom. But if I wanted to be an instructional leader, I needed to know what we expected from our teachers. I had just finished my Master's which had done little to redirect my pedagogical philosophy towards Outcomes-Based Assessment (OBA). The program was very traditional in its focus. It wasn't until I was quizzed, or rather challenged by a friend about my assessment views that I realised I needed to make the shift. He kept saying things like, "if we are teaching to outcomes, shouldn't we be only assessing the outcomes?" That was an important question because both of us were watching a lot of teachers assess the end product and thinking they were assessing the outcome. For example, if a cover page for an essay or project was not one of the outcomes, then why is it being graded and included in the overall mark. Or if participation is not a listed outcome, why are teachers marking participation. That was the first challenge to my thinking about assessment. In addition, I think we really need to challenge the practice of including homework for grades, especially if that is not one of the outcomes.

The next challenge to my thinking was around how we penalise students for not knowing the outcomes at the time of instruction. If a student is assessed on one outcome in September and demonstrates only a basic understanding of it then, typically that was the grade they got at the time of testing. But in November, I was testing another outcome that clearly required students to demonstrate the prior outcome in order to show they understood the new outcome, shouldn't we be going back and changing the grade of the first outcome to reflect that the student has a better understanding of a previous outcome? I really struggled with this, because I was trained that whatever a student got for a grade was what they carried with them into the final calculating of their grade. I was looking at assessment as defined by time, but if I really embraced lifelong learning, then why would I penalise students because they hadn't mastered the outcome when I taught it, only to demonstrate that they learned it later.

The next challenge to my thinking was around how we penalise students for not knowing the outcomes at the time of instruction. If a student is assessed on one outcome in September and demonstrates only a basic understanding of it then, typically that was the grade they got at the time of testing. But in November, I was testing another outcome that clearly required students to demonstrate the prior outcome in order to show they understood the new outcome, shouldn't we be going back and changing the grade of the first outcome to reflect that the student has a better understanding of a previous outcome? I really struggled with this, because I was trained that whatever a student got for a grade was what they carried with them into the final calculating of their grade. I was looking at assessment as defined by time, but if I really embraced lifelong learning, then why would I penalise students because they hadn't mastered the outcome when I taught it, only to demonstrate that they learned it later.

It took months of coaching, but I changed. Hence writing this blog. Maybe my story can be of help to others struggling with making the shift. So I would like to outline some of the challenges I see many teachers getting stuck with and preventing them from making the changes.

Take a few minutes to watch Doug Reeves video where he talks about changing our assessment practices to being more effective.

Although I didn't have the luxury to watch his video before I changed my assessment practices, he captures the essence of my journey. But let me highlight a few of the big changes I made.

Take a few minutes to watch Doug Reeves video where he talks about changing our assessment practices to being more effective.

Although I didn't have the luxury to watch his video before I changed my assessment practices, he captures the essence of my journey. But let me highlight a few of the big changes I made.

1. Don't combine multiple outcomes into one grading category

The traditional breakdown in high school for course outlines usually includes a grading policy. I was trained to write out exactly how the students were to be graded so they knew exactly how I was coming up with their grade. That meant that I clumped all kinds of summative assessment together under one category. Usually, it looked something like this for an English course:

Written Assignments - 30%

Tests/Quizzes - 20%

Major Essay - 20%

Final Exam - 30%

Looks about right, doesn't it? To prove my point, I Googled course outlines and found hundreds of similar examples that are still being used like this today.

What I found was teachers working with categories of activities where they did exactly what I was doing years ago.

2. Don't test more than one general outcome per summative assessment.

Why? There are a few problems with this approach. Let's first of all assume that there are eight general outcomes to be covered in this course. If we are teaching to outcomes, there needs to be one summative assessment per general outcome. Summative doesn't mean only tests or exams, but it can be an essay, a project, or a quiz. Essentially, it's anything that determines what a student can demonstrate with varying degrees of understanding at the end of the learning outcome. The curriculum may have three or five specific outcomes or concepts under each general outcome, but for reporting purposes, there needs to be only one summative assessment for the general outcome. I need to use a significant number of formative assessments for each of the specific outcomes or concepts that guide my instruction to ensure that students understand the general outcome before that summative assessment happens. When we add more than one outcome into the summative process, we lose the efficacy of the assessment process. It needs to be clear to the student to what degree they have achieved the outcome. If we add other outcomes to our assessment, it has a negative impact on validity. Validity is how accurately a conclusion, measurement or concept corresponds to what is being tested. How do we really know if a student has achieved mastery or not on an outcome if it's mixed with other outcomes?

2. Don't test more than one general outcome per summative assessment.

Why? There are a few problems with this approach. Let's first of all assume that there are eight general outcomes to be covered in this course. If we are teaching to outcomes, there needs to be one summative assessment per general outcome. Summative doesn't mean only tests or exams, but it can be an essay, a project, or a quiz. Essentially, it's anything that determines what a student can demonstrate with varying degrees of understanding at the end of the learning outcome. The curriculum may have three or five specific outcomes or concepts under each general outcome, but for reporting purposes, there needs to be only one summative assessment for the general outcome. I need to use a significant number of formative assessments for each of the specific outcomes or concepts that guide my instruction to ensure that students understand the general outcome before that summative assessment happens. When we add more than one outcome into the summative process, we lose the efficacy of the assessment process. It needs to be clear to the student to what degree they have achieved the outcome. If we add other outcomes to our assessment, it has a negative impact on validity. Validity is how accurately a conclusion, measurement or concept corresponds to what is being tested. How do we really know if a student has achieved mastery or not on an outcome if it's mixed with other outcomes?

Take Saskatchewan ELA 30A Outcomes for example; there are 10 total general outcomes, therefore, we should only have one summative assessment per outcome. Like I said, I may use lots of formative assessments with the different novels, poems, short stories, non-fiction literature that I use in the classroom. But I don't grade the students' understanding of the literature, but their understanding of the outcomes. The literature is only the medium I'm using to demonstrate the students can show they have met the outcome. So when I'm teaching the first outcome:

CR A 30.1 View, listen to, read, comprehend, and respond to a variety of grade-appropriate First Nations, Métis, Saskatchewan, and Canadian texts that address:

identity social Centres social

I may use multiple forms of literature to help students understand identity, social responsibility, and social action as it relates to First Nations, Metis, and Saskatchewan. But my focus needs to be how well students understand identity, social responsibility and social action, and not the literature itself. I don't need to have a chapter test or quiz on everything either.

3. Don't average grades to come up with a final grade.

Then there is the issue of combining the grades over two or three outcomes and then averaging them. Rick Wormeli says,"Just because something is mathematically easy to calculate doesn’t mean it’s pedagogically sound." Averaging is bad pedagogy. So take the above grading policy illustration, class work is 25% of the final grade. But every outcome has been combined into one category and averaged out for 25% of the grade. In truth, a percentage also tells us very little about what a student knows or doesn't know.Wormeli

I like what Todd Rose said aboutaveraging Average what the student

I'm a visual person and I need visuals to help illustrate for me. Look at this picture of a person on the right. It is multiple exposures over each other. What you are seeing is an average of all the pictures taken together. How clear is the picture? When we average our student's grades and combine everything into one picture or snapshot to give the students or pictures, this is exactly what we are giving them. It's not acceptable.

My preference is to use a 4 point system (Marzano) scale, where I list the outcomes using a bar graph color coded such as illustrated below. The summative results are used to determine the mark. If there is not enough summative information to determine levels of understanding, then formative results are taken into consideration.

Then there is the issue of combining the grades over two or three outcomes and then averaging them. Rick Wormeli says,"Just because something is mathematically easy to calculate doesn’t mean it’s pedagogically sound." Averaging is bad pedagogy. So take the above grading policy illustration, class work is 25% of the final grade. But every outcome has been combined into one category and averaged out for 25% of the grade. In truth, a percentage also tells us very little about what a student knows or doesn't know.

I like what Todd Rose said about

I'm a visual person and I need visuals to help illustrate for me. Look at this picture of a person on the right. It is multiple exposures over each other. What you are seeing is an average of all the pictures taken together. How clear is the picture? When we average our student's grades and combine everything into one picture or snapshot to give the students or pictures, this is exactly what we are giving them. It's not acceptable.

My preference is to use a 4 point system (Marzano) scale, where I list the outcomes using a bar graph color coded such as illustrated below. The summative results are used to determine the mark. If there is not enough summative information to determine levels of understanding, then formative results are taken into consideration.

The general outcomes are listed on the left and the bar graph illustrates where the individual student is at for each outcome. We had a policy in Saskatchewan that "if it wasn't a 2, it was a redo." Teachers emphasised to students on getting 2 or higher. In order to move forward into the next grade students needed to get a minimum of 2 in 75% of the outcomes. If they didn't, that's when credit recovery kicked in requiring the students to only have to redo the outcomes they had lower than a 2. Credit recovery recognises all prior student learning and assessments and does not penalise students for where they were, but acknowledges where they were now. During the course, we encouraged our teachers to go back and reassess student understanding when they demonstrated their understanding of an outcome had grown from a previous assessment.

If it is necessary by the Ministry of Education or for scholarship purposes to have a percentage, Saskatchewan Rivers School Division developed this modified Marzano conversion scale.

If it is necessary by the Ministry of Education or for scholarship purposes to have a percentage, Saskatchewan Rivers School Division developed this modified Marzano conversion scale.

Personally, I don't think it's necessary to convert from the 4 point to the percentage, but some folks need that

If you think for a second that the change has been easy, you’re wrong. I went to school and was graded one way. I went to college and university and was trained to grade the same way. It was when I really looked more deeply into this issue and realised the error of my ways. I made the switch, I had to make the switch. I didn’t switch for me, I did it for the students, because it was the right thing to do. I hope you see it too.

Tuesday, May 10, 2016

Our Student's Mental Health is More Important than Their Grades.

Tuesday, April 12, 2016

Do we treat academic mistakes differently from behavioural failures?

Recently I came behavioural centred sudent centred

I don't know about you, but has this been your experience? We go to great lengths to ensure students have second chances to relearn learning outcomes, fix mistakes, and retake tests or exams. All which are the right thing to do for students. We will reteach a concept until the students get it, but how different the story is when it comes to negative behaviour from students. We often assume that when a student misbehaves, they are willful and deliberate in their lack of respect for us. Students are then removed from the learning environment with little hope of being given an opportunity to relearn the expected behaviour ; even though studies show how long it takes for students to unlearn and relearn attitudes. I love the quote by John Maxwell, who said "once our minds are 'tattooed' with negative thinking, our chances for long-term success diminish.

It's so easy to forget about where many of these kids are coming from. Sadly, so many of the students with behavioural challenges come from broken homes, neglected home lives, uncommunicative parents, stressed out and even depressed personal battles. And all we can do is look past their hurts and fears to see the anger, defiance, and bad attitudes. It's so easy to pass judgment on these students when we have no idea what they are going through. I realize not everyone is like this, but it happens enough times to tell me we have a problem that we need to address and fix. I see students sent out of the classrooms to sit in the school hallways too many times to think that these are isolated incidents.

I was speaking to an elementary administrator recently, who recounted arguing with a teacher who wanted a student suspended because they were being defiant and refused to get their homework done and turned in on time. The principal was arguing that the teacher needed to take into consideration what the student was going through. He had recently been removed from his home because his parents were going through some marital issues, and he was living with a non-relative without any idea when he would be able to return home. And somehow his homework was the most important thing that mattered.

We have a dual mission as educators: 1) to teach these students the curricular outcomes, and 2) to guide and inform them in the virtues of life that form their character as the future citizens. That means we cannot be so detached in our role as teacher to only be concerned with teaching the curriculum. Yes, it's important, but how do you teach a child whose life is a mess when the last thing they want to do or can do is think about learning.

We need to think about whether we treat academic mistakes differently frombehavioural failures? I think we do, but what do you think? Maybe the better question is, "Would I want to be a student in my own classroom?"

We need to think about whether we treat academic mistakes differently from

Sunday, April 10, 2016

I Have my Opinions, But I'm Still Very Open-Minded!

I've never been one to shy away from controversy. Some might say that I can be quite opinionated. I would have to agree. I do hold some strong opinions about things. Lately, though, I find that I am less willing to share my opinions because I'm so tired of the intolerance. I may be opinionated but I am very tolerant of others opinions as well. In fact, I want to hear others express their ideas and opinions, because I believe that helps me learn as well. Many of the opinions I have held have been tweaked and modified because someone else made a good point that I hadn't taken into consideration.

While I'm opinionated, I have also noticed people being intimidated by another person with an opinion. That's the last thing I want people to feel around me. I want to hear what they have to say. Then there are those people who use their strongly worded opinions as a form of intimidation to keep people quiet and not oppose them. They use words like "That's stupid or crazy," because it shuts people up. This tactic is simply a means to shut down any further dialogue and indicate they are not interested in hearing another perspective.

Maybe it's because of my college days studying philosophy cross-legged on the floor in a circle in the professor's office that I learned the value of debating ideas, asking the right questions, and utilizing the Socratic method.

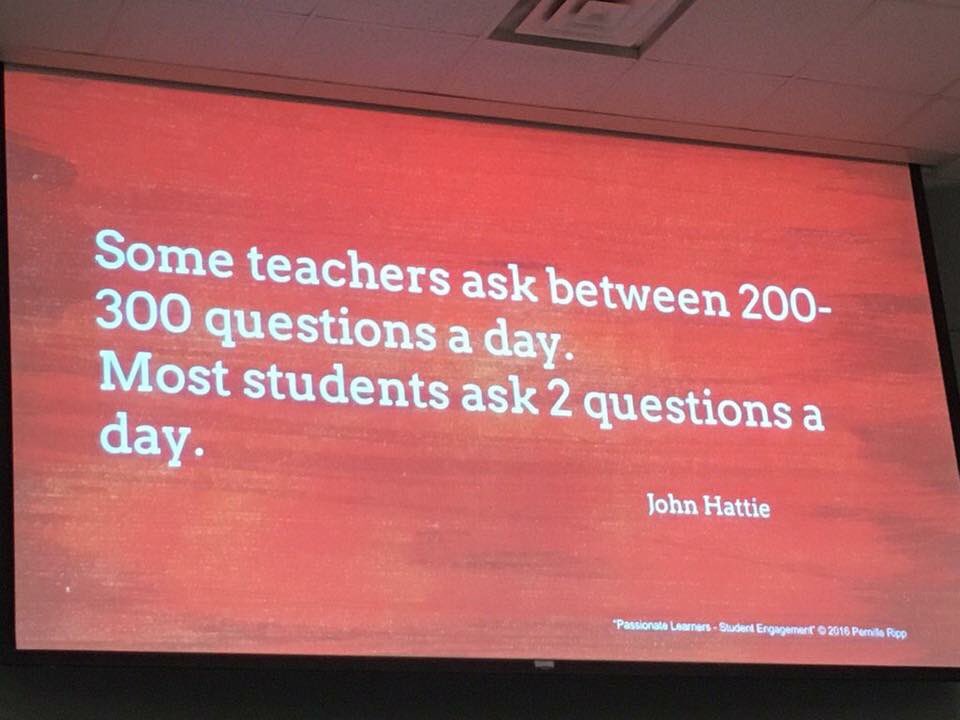

We were taught that the Socratic method was one of the oldest teaching tactics for fostering critical thinking. Using the Socratic method we focus on giving students questions, not answers. We inquire and probe a subject with questions. As a result, we explore elements of reasoning in a disciplined and self-assessing way that heightens learning. Yet, recently, I saw this quote sourced from John Hattie on Twitter that said "Some teachers ask between 200-300 questions a day. Most students ask 2 questions a day." I don't know about you, but there's something critically wrong with this picture. If students are engaged in the learning process, they will ask the questions. Our role as teachers is to engage in such a way that students are drawn into dialogue and discourse that causes them to dig deeper for their own understanding. So why doesn't that happen.

In a recent Gallup Poll, a couple of things were highlighted regarding engagement levels in schools:

Student engagement in school drops precipitously from fifth grade through 12th grade. About three quarters of elementary school kids (76%) are engaged in school, while only 44% of high school kids are engaged. The longer students stay in school, the less engaged they become. If we were doing this right, the trend would be going in the opposite direction.

About seven in 10 K-12 teachers are not engaged in their work (69%). And teachers are dead last among all professions Gallup studied in saying their opinions count at work and their supervisors create an open and trusting environment. We also found that teacher engagement is the most important driver of student engagement. We'll never improve student engagement until we boost teachers' workplace engagement first.

This falls completely in line with the quote from Ken Robinson, who said, " There is no system in the world or any school in the country that is better than its teachers. Teachers are the lifeblood of the success of the schools." While as a teacher and administrator, I wholeheartedly agree. However, there is some onus on teachers to first and foremost possess a positive outlook about students. Sadly, that's not always the case. I have worked in some extremely challenging school environments where teacher opinion or ideas was never listened to or considered. Yet, despite the difficult and hostile work environment, it was my love for students and their learning that kept me coming back day after day because I wanted to instill hope in the kids' lives. I didn't get into teaching for the paycheque or for a job. No. I became a teacher because it was my mission in life to give to students what I never received going to school. I had some horrible experiences as a student in school. I could hardly wait to get out of school. What awaited me in college clearly demonstrated how unprepared I was by high school.

Today, I love learning, and I am learning something new everyday I go to school to teach. I look around me and see families suffering from the loss of employment in this present economy, and I am grateful to be employed. I don't take it for granted. I don't worry too much about work conditions and how alone I feel in my role sometimes. It's not easy to lead, but I hope that I am modelling a hope and a care that I have for students, their learning, and their future. As teachers, sometimes we have to be extremely selfless and humble We make mistakes and fail miserably at times, but that's how we learn. So, yes, teachers are the lifeblood of a school, but they need to possess the ability to breathe that life into their students. Sometimes that means we need to change the way we are doing things, or have done for 20 years. Inherent in the word, "change" is the idea to transform, adjust, adapt, amend, modify, revise, or refine. We don't change for the sake of change or just to be different, but to improve something. That means we need to be open-minded despite our opinions and beliefs and consider the possibilities of improvement. So I've come full circle to where I started. Teachers have lots of opinions, and I love to hear what they have to say, but what I take exception to is; "That won't work," or "That's a stupid or crazy idea," or "I hate change." All which I have heard in the recent years. When educators discount any other thought or opinion in other adults immediately without any discourse, I have to ask, "is that how students feel in the classroom?" Discounted and dismissed?

How many times do students feel that way with me? I hope they don't, but I know I have messed up lots of times over the years. I still make mistakes. But I'm all about the growth mindset for myself and my students. And most importantly, I hope that students are engaged and learning in my classroom.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)